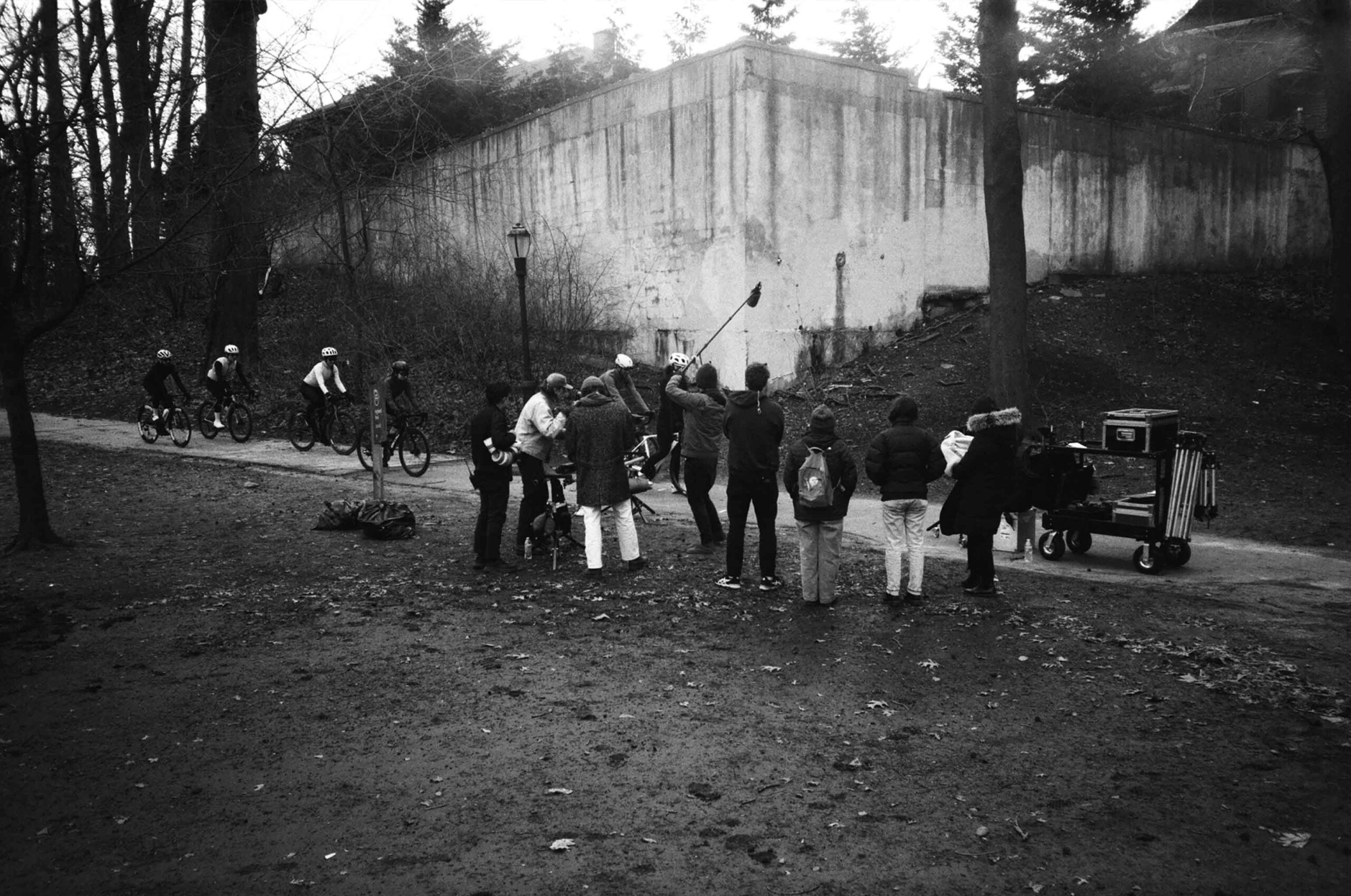

Behind the Scenes

The Cost of Greatness: The Story Behind ‘Useless Passion’

As a struggling athlete reflects on what drives her aspirations, the shadows that lurk behind the dream’s bright veneer come sharply into focus.

Director Bram VanderMark blends the meditative rhythm of a training ride with memories of moments lost, asking the audience to consider if the prize is worth the pain.

Bram has long been both a cycling enthusiast and a natural philosopher, so this concept provided him a unique opportunity to explore the ideas he has pondered. We had the opportunity to discuss the experience with him:

”"I was really struck by this question:

Bram VanderMark

Is passion meaningless, or meaningful? How do we define this in our own lives?"

Filmsupply: What inspired you to create “Useless Passion”?

I have a tendency to embark on these periodic deep dives. When I find interest in something, I don’t dip my toes, I cannonball to the deep end in pursuit of obsessive total immersion. Last year, I made a conscious effort to do this with philosophy, which is a boundless concept on its own.

Coming to the table as a total newbie, I decided that overview books would be a good place to start. Eventually, I came to Jean-Paul Sartre, and his quote: “Man is a useless passion.” He writes from a nihilistic, atheistic point of view, and he marvels at the lengths that man goes to find meaning in his life, to build something, to sacrifice for the sake of passion. I was really struck by this question: is passion meaningless, or meaningful? How do we define this in our own lives?

I had been wanting to create a film that involved a cyclist as, ironically, cycling is one of my passions! As I began to connect these two ideas, this concept emerged that allowed me to explore the hidden costs of passion and weigh them against the perceived benefits.

What is your approach to creative development?

Everything begins with a sort of compulsion that arises out of a thought or idea that I seem to be stuck on. When I’ve encountered an idea or paradigm that catches me, I begin to connect that idea with potential stories or contexts where it can be worked out or grappled with. From there, I begin writing in free-association, or writing with no constraints. I let any and every thought out for as long as it takes, and invariably, I start to see a through-line that may be interesting to explore. I narrow the idea a bit, and from there, I like to make a treatment. Although I may have no one to present this treatment to, the process is the reward – it helps me define the vision, the approach, and the aesthetic tone.

What is the most important thing you learned along the way?

The decision to shoot on 35mm taught me the importance of combining thoroughness with a high degree of trust in your directing intuition. At this point, shooting on film has become a bit of a revived cliche – we all know how people speak about the “process,” and sometimes that sparks some rolled eyes and a yawn from the outsider. However you choose to see it, shooting on film IS a particularly challenging and humbling process. Although we had a great HD tap monitor on set, we did not have playback. When you’re trying to prioritize an efficient schedule and an economic use of negative film, your brain is constantly nudging you to move on, move on, move on. Combine that with the rose-tinted glasses I tend to view my shots through on a shoot day, and I was finding it hard to know when I had GOT IT and when I hadn’t.

I may have spent two hours setting up a scene, working with the actors to rehearse, collaborating with the DP to find the perfect composition, and then ultimately rolling on two takes that felt great. Later, when we’d pull up those two takes in the edit timeline, I’d see a flaw that I completely overlooked on the shoot day, and that entire stretch of two hours that felt fulfilling and exciting would be rendered useless and woefully tossed to the cutting room floor.

Here we find the dance – you have to trust your intuition and move quickly and efficiently, but you also need to be thorough and patient enough to be fully convinced you’ve created the shot you’ll really need in the edit. This is the challenge we all face, and there’s no formula. I think my blunders and my successes on this project will move me towards being a better director. That’s the goal, and that’s really all you can expect of yourself.

Did you face any creative challenges during the development of the film? If so, how did you overcome them?

The original idea for the film was to shoot the entire thing in a continuous pan, emphasizing the cyclical nature of this kind of question. I had built it up in my mind that this was really exciting and fresh, and it shaped my idea strongly. Then, I tried it. I took my phone and tried to connect three shots and realized how constraining that approach would be. What now?? It always feels confusing and discouraging when a component of your idea is challenged or changed – but then, you step back, and you reapproach. I decided instead to focus on shooting in a way that was restrained and patient.

We primarily used locked off shots and slow dollies to invite the viewer’s attention to rest on the more subtle elements of each scene. In my experience, these kinds of self-reflection moments while training can cause time to crawl by and make it seem as though your training and pain will never end. By using these slow and static shots during the training segment, I think we were able to create a weighted and patient sense of timing in the cuts that conveyed that feeling well.

Were there any moments during shooting that stand out in your memory?

We shot for two days, and each day ended in a solo, late night drive to the Kodak Lab in Long Island City to drop off our film. I would be driving there in a state of both exhaustion and contentment , looking at the city skyline and the quiet streets, reflecting on the day. I get to shoot 35mm film with a special cast and crew of friends in New York City! These moments don’t come often. It was a special present to acknowledge and savor while I had it.

Did you encounter any surprises in the editing process that required a creative solution?

Absolutely! The process felt particularly prickly, as I edited the project myself. You don’t get the benefit of someone else helping you find what worked and didn’t on the shoot day. There were moments that felt so right on set, only to fall completely flat when I tried to use them in the edit . As a workaround for those issues, I began to stretch smaller moments to create breath, and shrink larger moments to create emphasis.

Originally, the bike trainer shots were planned to be much shorter – quick flashes of 1 or 2 seconds, and I envisioned the entire piece to be around 2 minutes. As I put the VO into the timeline, I realized that I needed more time. If every shot was quick, there was no room for the viewer to settle in and process what they were seeing, so I stretched the training moments to create that space. At the end of the day, you never really know what the film is going to be – you’re just trusting your intuition, listening to others, and trying new things.

What do you hope to accomplish with this film?

I wanted to use this film as an exercise in connecting a distinct philosophical question to a visual narrative. That sounds simple, and perhaps it is, but it also requires effort and practice, which I find so valuable! My hope is that this film conjures up a sense of resonance and reflection in the audience, and that it moves me a few degrees closer to being a better storyteller in the process.