Behind the Scenes

Fighting Forward: The Story Behind ‘Sorry You Have To See This’

How do you care for someone when their mind is under attack? Do our inner demons hurt the people we love?

In Sorry You Have To See This, director Josh Leong takes a stunningly raw and emotionally visceral look at the toll mental health challenges take on both the individuals who suffer and those who love them. We had the opportunity to talk with Josh about his personal motivations for this story and the unique approach he and his team took in telling it:

”" ...if this film teaches you anything, know that you’re not alone. Know that you’re not defined by rock-bottom."

Josh Leong

Filmsupply: What inspired you to create “Sorry You Have To See This”?

I think there are many ways to look at it, but I joke that this was an exercise from therapy that somehow became real. This film is largely inspired by a time in my life that I used to hate thinking about. Right before the pandemic, I experienced a really scary period of anxiety attacks and depression. It felt like a monster was living inside my head – pushing people away, hurting them, scaring them, and abusing relationships. I fought a war every day just to wake up and act like I was okay. All I wanted was to feel like myself, again.

Even with the support of people who refused to let me go, there were countless moments I wanted to give up on everything; to fall asleep and never wake up. I was exhausted more than I was in pain, and I couldn’t understand why any of this was happening to me. To this day, I’m still unsure why it happened or how I got better. But I couldn’t shake the feeling that making a film about it would be part of my journey to healing.

SORRY YOU HAVE TO SEE THIS is ultimately an imperfect attempt to put my raw emotions, memories, and nightmares on screen – told through broken, messy people – with the intent of affirming someone else who might be enduring something, similar. I was once told by a professor of mine, Alrick Brown, that filmmakers have a responsibility to “put our demons on screen.” Our stories fight our battles for us. And from the moment I started writing this film, I felt God beginning to transform an incredibly broken time in my life into something irrationally beautiful – something that wouldn’t just be a blessing to me, but to others, as well.

Are there any other artists or films you studied as you prepared for this project?

An enormous inspiration for this project was Luke Turner’s LOVE ME LIKE YOU HATE ME (which we shamelessly ripped a kitchen counter setpiece from). It was the first dance video I’d seen in which I was far more interested in the character’s eyes than their choreography. The story of a relationship was being told without any words – just faces, hands, and bodies.

Emotionally, I actually drew most inspiration from the online blog of a friend, Lauren Franco. Despite stumbling onto it, I found myself strongly attached to lines she shared in the aftermath of a “hellish week”: “The thing is, people will do or try to convince themselves to believe whatever they can to cope, usually to try to get around the pain. We try to convince ourselves that things didn’t happen, delete them, believe that we didn’t actually care or love, that it all wasn’t as important as it was. But I am finding that the best way to move on is straight through the wilderness, headfirst into the feelings. Trying to find a way around it just makes the journey longer.”

Words have a habit of speaking to our hearts in funny ways, and Lauren’s hit on a level that felt immeasurably convicting for myself. Beyond anything else, it was those four sentences that convinced me to persevere with any of this.

What is the most important thing you learned along the way?

Taking the pressure off the end result goes a long way. At some point during pre-production, I realized I didn’t care what anyone thought about the movie. I didn’t care if it was going to get into any festivals, or if it was too experimental. In fact, I didn’t care if the shoot completely fell apart (thankfully, it didn’t). I realized that the only thing that really mattered was how this film was transforming and healing my heart. I wasn’t making it to satisfy programmers or to climb the career ladder – I was making it just for me.

Did you face any creative challenges during the development of the film? If so, how did you overcome them?

One of the biggest challenges during development was deciding whose perspective to take – did the story “belong” to Ellie or Nathan? It had a significant effect on the meaning of the film and how it should end. Initially, I felt like the film should be Ellie’s story: a deeper, more sympathetic look at the caregiver’s burden. But it didn’t align with how I wanted the film to close. I felt it was most realistic to have Nathan revert “back to type”, in the end. It was important for the audience to understand that it’s Nathan’s decision to wash the dishes, again.

As such, I began to see the film more from his perspective. It wasn’t a romanticized look at how caregivers magically heal all our wounds, but it’s certainly a tribute to those who get us through those tough moments. Ultimately, Nathan gets to thank Ellie via voicemail at the end of the film, but tragically, he’s still left with his own demons.

To me, mental health often looks like an ongoing battle. It would be insincere of me to frame issues like this into a quick-fix narrative about our relationships and thought-life. That simple perspective shift helped unlock new moments in the screenwriting process, and the film ended up opening with Ellie but closing with Nathan.

Were there any moments during shooting that stand out in your memory?

Due to timing and lighting constraints, we actually shot the last bedroom dance, first. I was nervous that it would be difficult to get our actors into the right headspace, given it’s such an emotionally charged scene, but Josh and Julia ended up blowing everyone away, even on the first take.

Each of our dance sequences were a gauntlet of painstakingly-choreographed movement combined with a dynamic one-take. It essentially required three dancers operating at their best – our two leads, and our DP, Cece Chan. If a mistake was made, we had checkpoints for anyone involved to call the take off and restart. We ultimately ran the bedroom dance three times, and our actors nailed every single beat. It was a heart-in-my-mouth moment just watching from monitor – and I wasn’t even the one performing! But it was always a celebration when they pulled it off, and it’s a testament to the rigorous preparation and talent required of our actors to nail it when it mattered most.

You employed a unique mix of traditional blocking and dance choreography. What led you to this approach, and how was the experience?

This was something I workshopped extensively with our choreographer and movement director, Katherine Maxwell. From the beginning, we decided it was important to retain a level of “pedestrian” movement to our narrative components. The film needed to stay grounded, despite its more experimental, dance-like sequences.

Our process started with me sharing my personal journey and the mess of emotions associated. Katherine did an incredible job of picking through my word vomit, identifying themes and throughlines that could be anchor points for the dances. In my head, the movement sequences had very little form – but together, we were able to distill a narrative structure in all three dances by identifying each character’s objectives and doubts. I often joke that our initial calls felt like therapy sessions for myself! Not only was Katherine a patient listener, but she also guided our discussion and ideation to places that ended up being really healing.

On set, this was also my first time working with a movement director. I’ve still got a lot more to learn in this arena, but it was a really collaborative and rewarding environment in which Katherine and I traded time with Josh and Julia, balancing both acting and choreography notes.

Did you encounter any surprises in the editing process that required a creative solution?

Pace was always an issue. Given our long takes, the film always felt a little too slow. I ended up speed ramping significant portions of our narrative sequences, keyframing around movement to keep things smooth. It ended up cutting almost two minutes from our total runtime, which I think helped the piece, overall.

Sound design plays a huge role in the telling of this story. How did you approach that process?

From the beginning, I knew I wanted sound design to be front and center. The film essentially runs on two independent, parallel storylines: the visual world and audio world. Sometimes, what you hear directly juxtaposes the emotion of what you see. Dialogue is presented through phone calls, and the caller perspective constantly changes. Additionally, sounds commonly transition from being non-diegetic to diegetic, effects pan in 360 space, and the audience doesn’t always hear exactly what they’re watching. Sounds confusing? Great.

I have to give major props to our incredible sound designer, Vinny Alfano, who was fully down for the ride. We decided we wanted to swing for the fences – always erring on the side of trying something new and experimental. We built a new structure for notes and “rules” about what we hear (that were often broken). The goal was to create something so unique and immersive that you could close your eyes and simply listen to the film.

The sound design was additionally supported by a gorgeous score from Caroline Ho, who was also willing to experiment with new textures, motifs, and themes. We played with everything from rising VHS static whenever Nathan’s thoughts start to swirl, to heartbeat-like bass drum pulses and heavy breathing during the dances. The result is something really exciting, and I strongly encourage viewers to experience our team’s crazy ideas on nice speakers or headphones.

When did you know this film was going to be truly special?

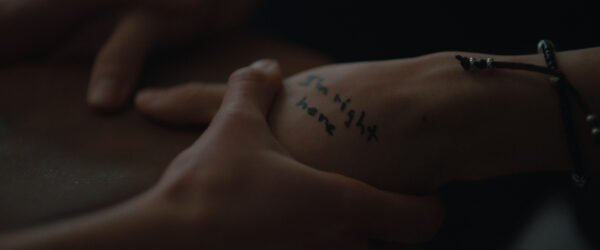

There’s a moment towards the end of the film after Ellie gives Nathan her necklace and traces his face. They lean in, forehead to forehead – and I still cry, every time. That moment, to me, represents unconditional love. The kind that would refuse to leave, even in the midst of chaos. It’s a tribute to the people who are the only ones who stay, and it’s a special moment to me because it reminds me that the only reason I’m here today is because there were loved ones who did that for me, too.

What do you hope to accomplish with this film?

Simply put – when someone watches this film, I hope they can feel seen. During my own season of depression, I seemed to do everything to convince myself that I was alone. I was addicted to piling pity on myself, and it felt like I could never feel normal, again. In a way, this film stands to prove that it’s possible to smile again. It’s possible to look back and mourn what was lost while being grateful for what happened. It’s possible to transform something that was broken into something new.

For years, this part of my life was filled with shame and fear. Yet though this film, I’ve consistently received a vision of overflow – of people emerging from the woodwork, being touched and feeling seen by work that came from a painful place of vulnerability. To those hurting and to those sharing their burden – please don’t give up. I’m not promising a fairy-tale ending or a five-step solution, but if this film teaches you anything, know that you’re not alone. Know that you’re not defined by rock bottom. In the words of my friend Lauren, “it is the will of a good God to make us better than we once were.” And even if it took years – making this film was proof for me.