Behind the Scenes

Finding a Greater Purpose: How Director John Matysiak Brought the Story of Checkers World Champion Marion Tinsley to Life

We were put on this earth to do great things, and those willing to rise to the occasion may find themselves becoming true masters of their purpose. In King Me, Director John Matysiak, in partnership with Nashville-based production company Stout, uses a hybrid of documentary and narrative filmmaking styles to bring to life the story of American mathematician Marion Tinsley. Through hard work, dedication, and extreme focus, Tinsley would rise from humble beginnings to become the greatest checkers player who ever lived.

”“Most people have played checkers, the rules are fairly simple, but to master the game as Tinsley did elevated the game to another level of prestige and finesse.”

John Matysiak

FILMSUPPLY: What was it about Marion Tinsley’s story that inspired you?

Before this project, I can honestly say I did not know much about Marion Tinsley or even that checkers had world championships and rankings just as chess does. The more we learned about Tinsley, the more inspiring his story became and the more we wanted to include it in the film. At some point we had to narrow things down, but what a unique story and unique journey of what it means to devote one’s life to a singular purpose and goal. His story begs to be explored further.

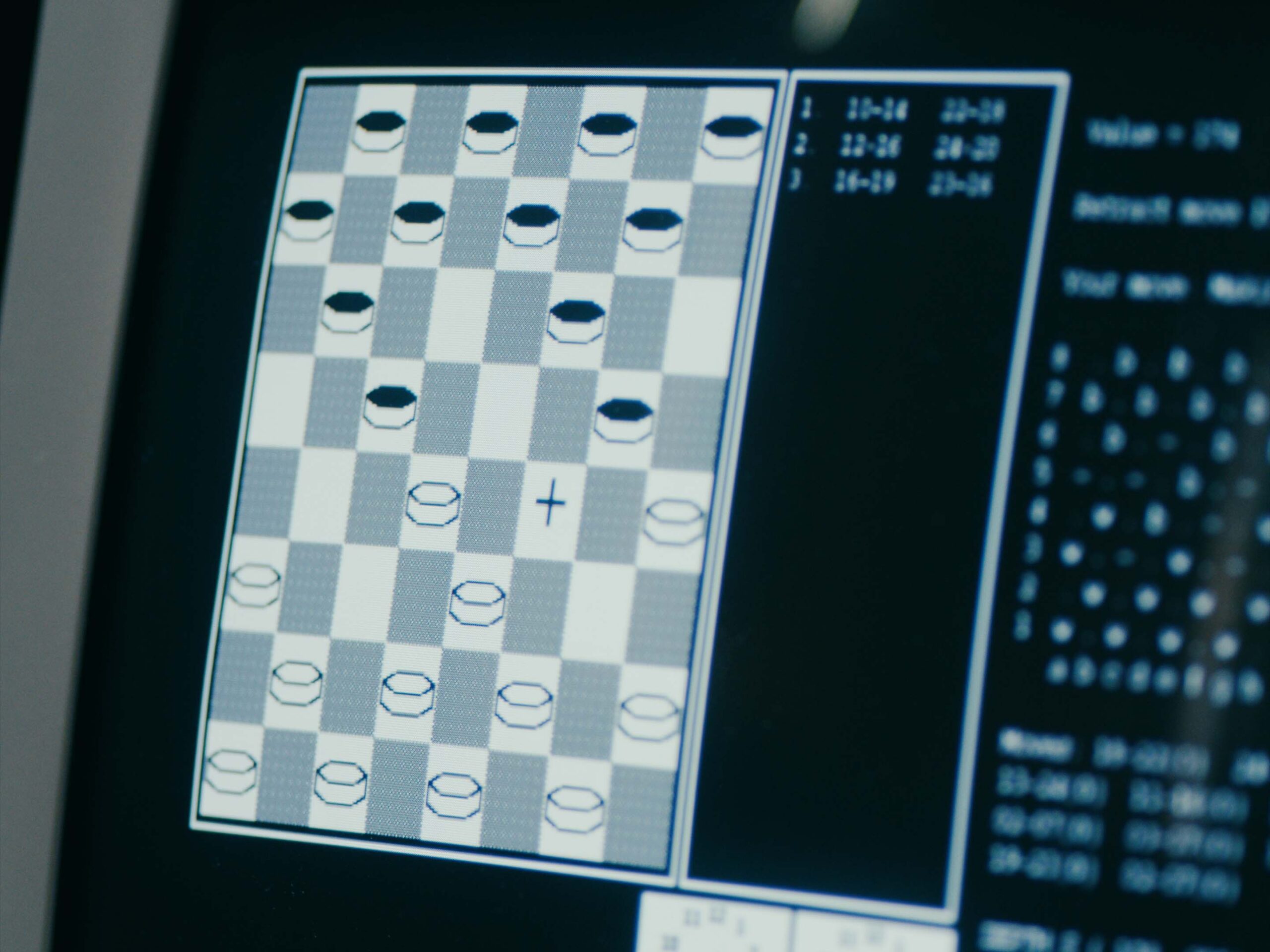

I personally found it fascinating that while computer programs were being developed for chess, here there was a computer programmer deciding to use the game of checkers in developing an AI program. This larger theme of AI and our relationship to AI really came about from learning more about Jonathon Schaeffer (Chinook project leader) and his story: how he was on his own unique journey, and his desire for perfection but through a computer program.

What were the biggest challenges in telling this story?

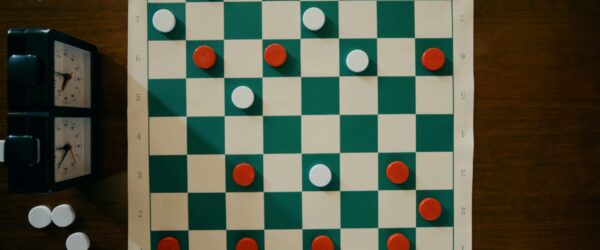

For us, one of the biggest challenges was how to show the audience the nuances of the game of checkers. We all know chess to be full of strategy and different moves and openings developed over the years but we rarely look at checkers through a similar lens. This was an opportunity to begin to explore the game and its place within culture and history. Most people have played checkers—the rules are fairly simple. But to master the game as Tinsley did elevated the game to another level of prestige and finesse.

You served as both the director and the cinematographer for the film. What was your approach to developing the film’s visual language?

It’s hard not to look at a film about a board game like chess or checkers and not be inspired by Steven Meizler’s work on Queen’s Gambit. I think more than anything it gave us the confidence to know it was possible to create our own specific visual language for King Me and the game of checkers in general.

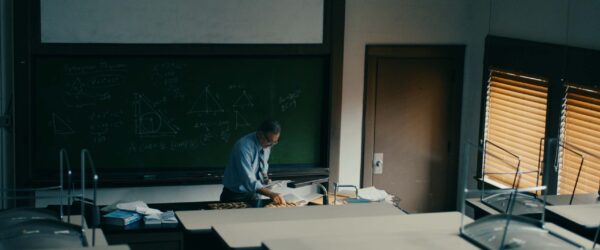

We knew the film would have a pretty significant VO component which lent itself towards being a bit of a hybrid between traditional narrative and documentary techniques. I always saw the film with a taller aspect ratio, which went hand in hand with the aspect ratio of a checkerboard itself, so it just sort of made the most sense. There was a moment we considered shooting the film with anamorphic lenses to really showcase the scale of his achievements and the grandeur of the story, but ultimately Tinsley was a modest man with a humble background that never saw his accomplishments more than what they were, so the 4:3 aspect ratio just felt right for his story.

In terms of the visual language, I’ve been so inspired recently by what is being done in the documentary space with compositions and stillness with the camera, letting the action play out without getting in the way of it. When done effectively it’s extremely powerful and forces you to lean in and engage with the film on a deeper level.

What was it like working with actor William Kalinak?

It’s not until the end of the movie that I think some people even realize that Marion Tinsley is played by an actor, again which leans into this idea of our film as a hybrid between narrative and documentary in our approach.

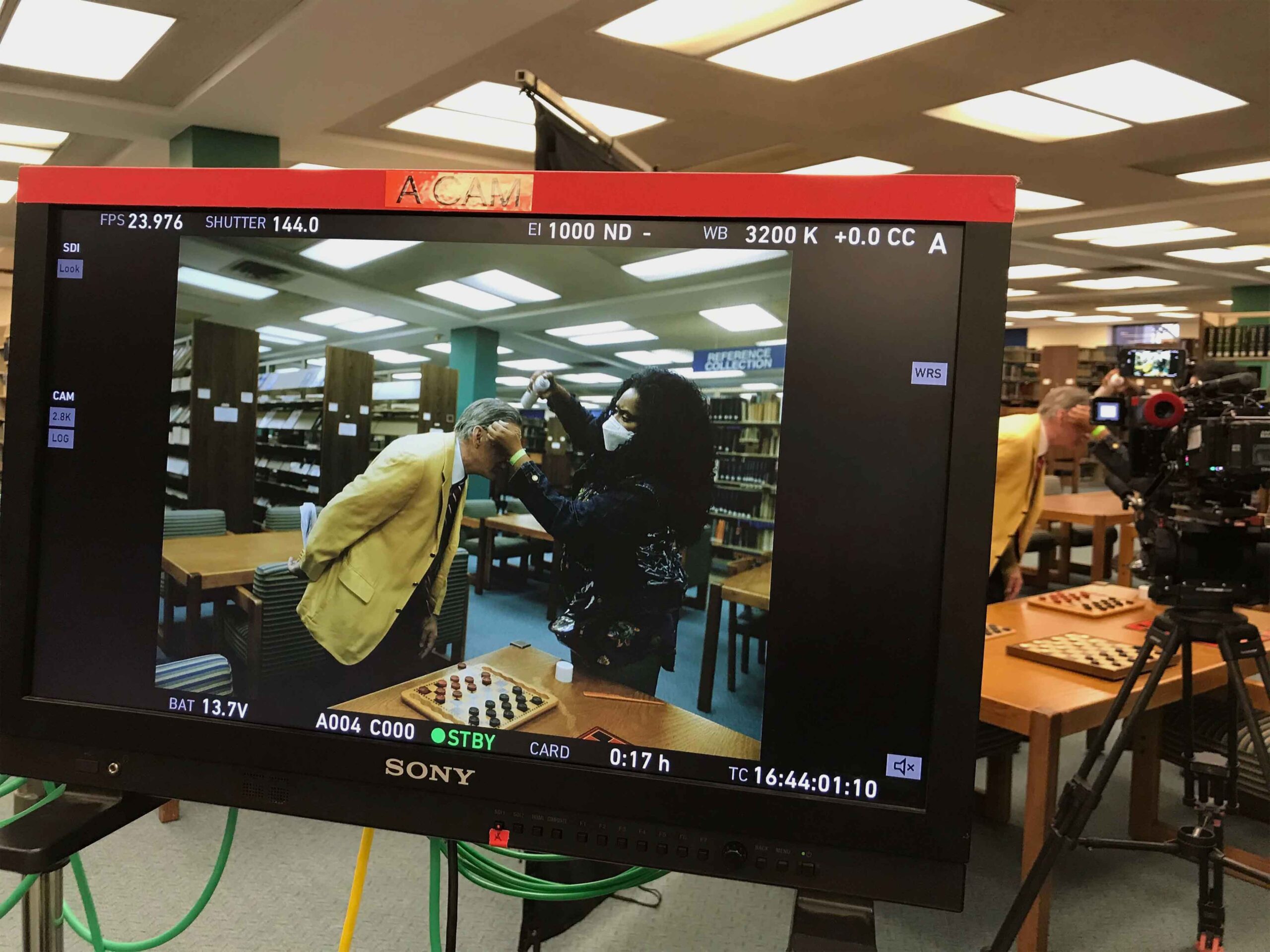

I can’t say enough about what William brought to the table on this project. Through a casting director, we put out a casting call and went through tape after tape and tape, and then we saw William’s tape. Here I was looking at an audition tape of what essentially was Marion Tinsley, reborn or channeled or however you want to explain it. William had completely transformed into the character, his voice, his posture, his mannerisms, it was uncanny. He found glasses that magnified his eyes slightly, he made devices to push his ears slightly. He fully embodied this character.

When I first met him for the wardrobe fitting I was actually shocked at how young he looked compared to his audition tape, it was a true transformation once he got into hair, make-up, and wardrobe. William the actor disappeared and what was left was Marion Tinsley. I look forward to the chance and opportunity to work with William again.

What was the biggest challenge you faced during the shoot?

The entire film was shot in a single day, so the biggest challenge we were up against was the schedule and not wanting to drop any of the locations and scenes. I was fortunate enough to work with some of my long-time collaborators as department heads and that made things incredibly efficient. Geoff Storts was our 1st AC and Justin Hughes was our Gaffer.

I remember shooting the overhead shot of the checkerboard and by the time we finally got the rig over the table set we shot for about 30 seconds. We quickly moved some of the checkers around in some type of mock game for another 30 seconds and we moved on. That was how we shot the entire day. It was just one of those shoots where you had to be mentally setting up the next shot in your head while you’re currently shooting the shot you are on to stay ahead of the schedule.

If we had a moment, we would improvise or do some type of variant. One such sequence that was improvised was when Tinsley is sitting in the hallway on the floor playing checkers. We knew we wanted a shot of him walking in and turning on and off the lights, but it was until we were in that hallway that we just decided, “Hey, maybe just sit down against the wall here and set up books around you as if it’s after hours and you’re playing checkers.” It ended up being one of my favorite visuals of the film.

Were there any surprises or challenges during post-production?

I remember having a first cut pretty soon after we wrapped. It came together pretty much as scripted just based on it being VO-centric, but then there was this whole other layer that went into the last 10 percent or so that really took the film where it needed to be. We were all so passionate about the film that I think we all wanted to make sure we didn’t leave anything on the cutting room floor. A lot of options and ideas were explored trying to finish that last 10 percent if that makes sense.

The film has a great score that fits the tone and story perfectly. What was the process for designing the sound of the project’s music?

Jordan Lehning is a genius. We met on Old Henry, and his score elevated that film beyond anything I could have imagined. To this day, I will sometimes just put the score on and listen, so much so that my kids love it as well now. It’s haunting and mesmerizing, it puts you in a time and place like nothing I have ever experienced. It’s everything you want in a piece of music that while it complements the film it also stands completely on its own. With King Me, we had always talked about the idea of getting an original score done for the piece but sometimes that’s not always possible on a short film or a short piece like this, for a myriad of reasons. I reached out to Jordan first to see if he was even available to jump on to short-form projects like this, and what really helped is that we were pretty flexible on our timeline and able to work around his schedule. I had some initial ideas, but really wanted Jordan to run with it. In our first conversations, we spoke about our mutual love for Phillip Glass and there was something about the rhythmic nature of his work and his willingness to break from convention that Jordan and I both got excited about. The first time I heard some of the themes he put together I knew we were immediately in the right direction. His use of bass clarinet right off the top was pitch-perfect. Growing up, I was a classically trained musician. My parents were both music educators and teachers so it was really nice to be able to collaborate with Jordan on a detailed level. Music makes such a huge difference in a piece. I really loved what Jordan brought to the table, his instincts were so perfect for this film. My only regret is that the film isn’t longer, which would mean more of Jordan’s score.

What do you want audiences to walk away thinking and feeling after they watch the film?

If nothing else, I want the audience to know more about Marion Tinsley than they did before they watched our film. He lived such a humble, spiritual, and modest life, and the idea that someone could stumble across our film and hear his journey and be inspired in some way by his story, that to me would be beautiful. And I think it’s what Marion would hope for as well.

What are you working on next?

I just wrapped up shooting HBO’s Winning Time Season 2 and actually have a George Foreman biopic being released in theaters in the next month or so. In the meantime, it’s been amazing just being able to be home to help coach my son’s little league baseball team.