Innovative film editor Lucas J. Harger approach to his work is about as far from clock-punching as can be imagined, and hearing him speak of process evokes thoughts of ‘The Method’ school of acting, but applied to post work. An Emmy winner for NBCSN’s hockey special The Road through Warroad, Harger has cut a variety of projects in recent years, ranging from commercial and promo work for Microsoft, Amazon and Anheiser-Busch to the proof-of-concept film The Heights and the wrenching short Sleep Well, My Baby. SWMB depicts the personal cost to victims of human trafficking that earned a Silver YDA at Cannes.

Harger finds that when he can join a project early, it provides a greater opportunity for him to delve deeper into the relevant subject matter. “Having the mindset and approach of ownership starts to separate some editors from the rest,” he notes. “An editor takes it upon himself to be a torchbearer, on behalf of the director, the subjects, the world being built, and the story being told.”

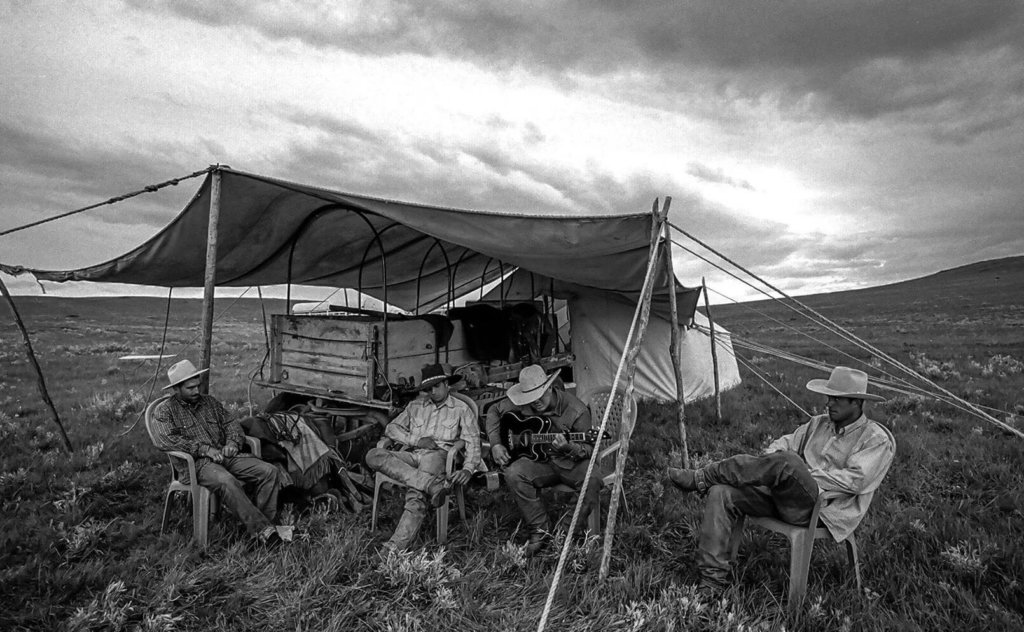

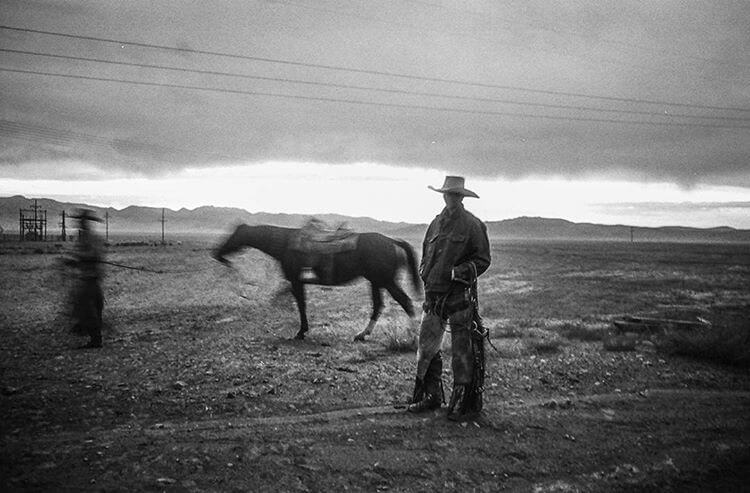

That level of immersion is aptly demonstrated by his work on Cowboys: A Documentary Portrait. The film, co-directed by Bud Force and John Langmore at 1922 films, featured shoots that encompassed several cattle ranches spread through a number of western states, depicting the workaday existence of contemporary cowboys carrying on the ways of their 19th Century forebearers. “The cowboys here are real freak’n cowboys,” Harger declares. “It’s difficult to find stuff in the film world on real cowboys.” Realistic depictions of the working life of a cowboy have been fairly limited, but include such notables as John Huston’s film of writer Arthur Miller’s The Misfits and writer/director Tom Gries’ Will Penny.

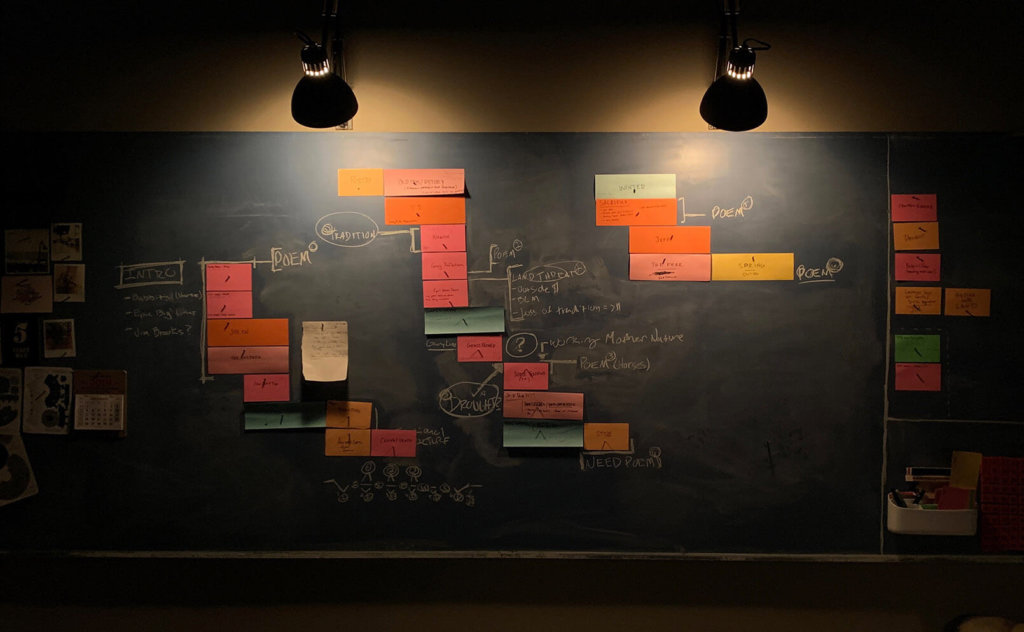

Having come on after about seventy percent of shooting was done, Harger was able to review the footage and interviews before embarking on the cutting, an approach allowing him to ease into the production process while still affording him time to research the history of cowboys and the west. “On Cowboys, I bought a ton of books – some historical, some memoirs, plus some classic western fiction,” he explains. “Reading up on things took a good part of the three months of time I had to get going, letting me get versed in this world, which was something well apart from how I grew up in Michigan.

“Besides the obvious tropes of cowboys and the west, this was new territory for me,” Harger continues, “so a large amount of preplanning related to the ‘meta’ aspect of the west rather than specifics of the cut. I had deep conversations with the directors that let us determine which tropes to avoid and which avenues merited exploration. Some of this was thinking about what constituted ‘western’ and what didn’t, in the authentic sense of the word. So it was a matter of thinking about how to utilize the landscape, with its iconography, without mythologizing these figures, keeping them real and situated in these vistas.”

(Photo Credit: John Langmore)

Harger found the use of poetry — S. Omar Barker’s “Into the West” — was an effective frame for the visual material, which he was also able to influence by requesting pickups that could possibly enhance the edit. “Fortunately, there were a couple of cowboys available to shoot pickups when we needed connecting tissue to link up disparate elements.”

Harger also considers the decision to not cut among the most powerful of tools in the film editor’s repertoire. “There’s a moment in the film when Jolyn [Young] is talking and she stops – and we stay there with her, holding for five to ten seconds, but it’s worth it because we’re seeing and feeling her come to a realization about herself. That moment is the one connecting her with the audience. If you edited that in a conventional cut and chop way, it would undercut that moment and cause the audience to miss out. Holding instead of cutting is just as powerful an editorial tool. Sometimes overuse of a particular technique can come off like propaganda, so the characters seem to be getting used as mouthpieces instead of giving off the exciting vibe of a real person honestly expressing themselves.”

Getting back to his philosophy of immersion and collaboration, Harger describes the role of editor in the documentary world as one that should become considerably more holistic than is usually evident in 30-second, 60-second and branded content work. “When I start work, the captured footage hasn’t always been reviewed by the director, because they haven’t had time to sit and take in 10,000 feet of material. I do get to do that, and my fresh eyes can see not only what was intentionally acquired, but also elements that can be applied out of their original context that will still help visualize some truth. There’s never a one-size-fits-all for every story, so though you start out playing in the sandbox created by the director and/or the editor, most often the sandbox is one created by the film itself, with the filmmakers becoming a slave to the project — meaning you’re chasing it.”

Harger’s only hard-and-fast rule about assignments is that this chase is a collaborative one. “I want to be down in the weeds with the director finding the story, rather than having things laid out for me up front that goes a-b-c, 1,2,3,4,” he emphasizes. “That sort of set-in-stone approach is a red flag to me, because if I see the footage and think the story is heading in another direction – that the imagery shot is evocative in a way that seems at odds with his intent – then I wouldn’t know why I was there. An openness and willingness to explore and find the movie within the material is the key. I like to fulfill the role of a partner with the client, working in collaboration with them. I find that by being there during most of the course of the project is the best way to provide that service and maximize my contribution.”

Harger finds that a lot of played-out visual tropes are turning up in documentaries as of late. “If you research their origins, you’d find some honest and creative approaches,” he acknowledges, “but they’ve since been ritualized into the formula. A film starts to become dishonest by forcing these by-rote approaches on the material instead of letting the originality and spirit of the thing guide you, applying somebody else’s visual language to your story. Everything under the sun has already been done, sure, but how you combine all the visual, aural and narrative components to shape this particular film should be its own thing, not the ritual piecing together of a Frankenstein’s monster. You want to see that unique new personality, and so you must fight against falling into those kinds of traps. Staying open to letting the film speak to you and tell you what it wants to be is a key.”

Sometimes that means taking roads that dead-end. “On Cowboys, Bud, John and I tried certain things in the cut that would have been great to use in a different film, with truly beautiful imagery, but it didn’t feel authentic to this film. That only became evident when we discovered the core of the matter, at which point you have to be ruthless and leave whatever doesn’t support that hard-earned feeling of authenticity.”

With respect to his work process, Harger likes sound workflows that allow things to be done in a clean and logical manner. “I refine and revise specifics all the time, but the particular NLE is irrelevant to me,” he admits. “I do spend a lot of time on workflow, especially on feature work, because there is potential for a ton more footage and mixed camera formats, and therefore many assets coming into your workstation to manage, which means a really robust workflow is essential. Mapping out what kind of media is being used and determining whether we want to use a team project approach or use proxy media are always needing to be worked out. What I really try to stay on top of is developing control surfaces that work for me. I like having some unique button layouts so I look for ways to improve on my physical interface.”

Whether the work is a documentary, promo/commercial or feature film, Harger states that the fundamental tenets of drama, such as weighing suspense vs. surprise, still apply. “The work needs to be entertaining and emotional, so you look for moments when you can create tension, or empathy, some kind of connection between the subject and audience; that’s the core fundamental,” he concludes. “It doesn’t even necessarily have to be a positive connection, but something that gives them a way in. With most documentaries, you don’t have a hyper-controlled environment to play in, so you look for ways to heighten or omit in order to create hills and valleys like a dramatic feature. But, that happens through exploration. If you have a preconceived notion of what the film should be, you probably shouldn’t be an editor. Sure, if you’re just assembling pieces, you can get it there in the end, but to me, documentary work is 100% exploring, a process of discovery, and at some point, the film takes on a life of its own, with a unique personality, and you’re just ushering it along so it doesn’t fall down and kill itself.”

…documentary work is 100% exploring, a process of discovery, and at some point, the film takes on a life of its own, with a unique personality, and you’re just ushering it along so it doesn’t fall down and kill itself.

Lucas J. Harger