How do you package concepts like freedom, patriotism, inclusivity, and war into one neat package? For most agency creatives, it may seem like an insurmountable task, a brief you’d rather not see come across your desk. But, for Vida Cornelious, the answer was simple: Be authentic.

“The industry may tell us to chase a trend or a fad, to run towards that shiny object,” Vida told us. “But, the best way to get authentic work out of yourself and make things you’re really proud of is to be true to your voice. And be true to the message that you’re putting out.”

Vida is currently the Executive Creative Director at The New York Times’ T Brand Studio, and when we asked her about one project that’s shaped her career, she reflected back on her work with Jeep. As the creative director with GlobalHue at the time, she was integral in reshaping the iconic car brand for a new generation and a new demographic.

In our conversation, she tells us how she and her team won Jeep’s heart with their new vision for the brand, and how they produced an inspiring Super Bowl campaign by writing from the heart.

Filmsupply: Could you walk us through your career?

Vida Cornelious: I’ve been in the industry going on almost 30 years now. I started at UniWorld Group and then moved over to Burrell Communications Group, both of which were very large multicultural firms at the time. I did a long stint at DDB Chicago. I learned really valuable information that I lean on to this day, in terms of how to ideate properly, think through your creative, and develop your creative process and voice.

Then, an opportunity came for me to go and actually lead a creative team, restructure an agency that ended up being GlobalHue. It was a really ripe opportunity for me to come to this agency and really help them develop a new way of working creatively. The first opportunity that I was pitching there was for the Chrysler business. With new leadership coming in from Italy, their CEO Sergio Marchionne and his team really wanted to open the aperture to all the agencies on the roster to have an opportunity to pitch business.

He believed that ideas can come from anywhere. So our team, having an opportunity to pitch on the larger slice of the pie, if you will, was a new opportunity for GlobalHue. For me personally, it was actually lined up perfectly with what I have been trained to do from my time at DDB.

Do you think the multicultural aspect of your experience influenced the creative side of your work?

One hundred percent. It creates a deeper understanding of insight and strategy, being able to understand the nuances of how cultural influence can affect creative output or execution. Many times in those roles, you’re working as a partner agency to the general market agency. So, even if they’re strategically setting the vision for a particular project, you still need to take those inputs and try and understand how they best are nuanced for the audience that you’re talking to.

It really gave me a wider understanding and appreciation of all types of consumer segments, to be sensitive to the cultural understanding of a particular message and how it can be perceived. I’ve always kept that in the back of my mind. What does that emotional quotient become for anyone who’s receiving the message that I’m trying to write?

Do you have a specific example of that playing out?

A big one was actually with the Jeep project. Strategically, the brand itself always lived in a space of freedom. Freedom for their general consumer meant freedom to go where they wanted—up into the mountains, forging rivers, and rock climbing. But, freedom for people of color and indigenous peoples has a very different meaning. Freedom means expression. It means the ability to succeed. It’s tied very much to the historical context of those individuals.

So, when we were thinking about how to revamp the brand for them, we had to reframe freedom in a context that worked for both segments. Freedom was no longer about going anywhere, doing anything. It was about possibilities. It became an inclusive message based on understanding an insight into other audiences.

What was it like pitching a brand-altering concept to Chrysler?

It was intense. I want to say there were at least five agencies that were on the roster at Chrysler and all of them were asked to pick a brand and pitch it. Our team decided to submit pitches to Dodge and Jeep. Both of those pitches made it to the final round. Our team ended up going all the way to the end with Jeep and that was the one we were awarded. It ended up being our agency of record responsibility.

It was a really big win for us. It did ruffle a lot of feathers in the industry. At the time, their current agency had lost the business. There was a philosophical shift at Chrysler at the time because of the new management. We were coming off of the bailout. There was just a perfect storm of why things needed to really be upended, so to speak. It gave our team an opportunity to really restructure properly, to lead the charge on one of the most beloved American car brands.

Why do you think you won the pitch?

We turned the vehicle into a lifestyle brand. Prior to that, the client was banging their head against the wall, trying to sell the vehicle to the same person over and over again—a middle-aged, Caucasian male who likes to take the Jeep out on the weekend, ride until the wheels fall off, bring it back dirty.

What they weren’t realizing is that there was a barrier in that. It’s a badge of honor in driving a car until literally the wheels fall off. So if you’re trying to sell that car to that person every year, you’re going to wait 15 years to do it because that’s how long they want to keep it. We said, “Hey, this is an opportunity to turn this brand into a lifestyle brand and the lifestyle doesn’t have to just be a weekend lifestyle.” So, that’s how we developed the core value of freedom and the fact that the brand represented something broader for more people. It set us on the right path.

Inclusivity makes sense from a business perspective, too.

Totally. Let’s go from talking to the 5 percent to the 95 percent, but in a way that doesn’t alienate the 5 percent. There was a hardcore community associated with Jeep. I mean, even to the point where there was some friction about women driving Jeeps. It was very much a boys’ club in that way. It was a really interesting challenge to solve.

I had an amazing strategic partner who was very, very astute about understanding how all of those insights needed to come together. Cracking that conversation open was exactly what the brand needed at that time.

Let’s talk about developing the Super Bowl spot.

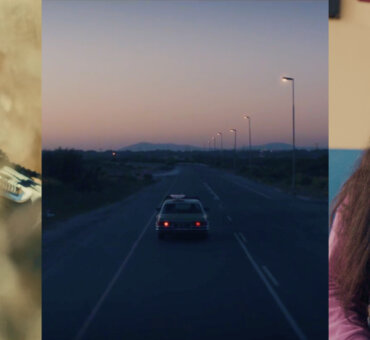

At that point, we had the Jeep business for almost five years. We were seeing all of the social media bubble up around the announcement that President Obama wanted to bring all of the troops home from Afghanistan. We thought, Wow, what an amazing opportunity. These soldiers may not know what they’re coming home to, but we can welcome them home. We can be the official vehicle that makes sure that they get home, literally, to their doorstep.

So, the initiative started with a pickup at the airport. We’d drive these soldiers to their destinations. We dug into the history of the brand and Jeep was one of the few brands that actually had skin in the game. In 1941, it was literally built as a government issue transport, a “sheet-metal soldier” for the military. We felt that if anybody had the responsibility to take these men into war, as well as bring them home, it would be us.

It was not a hard sell with the client. We ran into a lot of challenges from an insurance standpoint, to be able to literally do pickups and drop people off. So, instead of doing the actual pickups and drop-offs, we partnered with the USO and created the commercial to back it. For every person tweeting or hashtagging OSR, Operation Safe Return Jeep, we donated a dollar to the USO.

How did the actual spot come together?

It was an incredible journey. We learned so much about military families, about what they really are fearful of, and how to create a message that felt authentic. It was a really collaborative process with our client. I ended up writing the spot myself, but it was after many rounds of pushing the team and helping them understand how to get to that emotionally charged place.

We were inundating ourselves with military videos, and videos of people sending loved ones notes. Interestingly enough, it was the videos we found of pets that go nuts when their owner comes back from war that inspired us. Here’s an entity that doesn’t speak, but there’s this core feeling of being missed. It’s felt by everyone, all the way down to these animals. We really started thinking about that and digging into it.

We also ran across a video of a soldier who said that his biggest fear was not being killed, but being a stranger in his own home when he came back. We realized America really is not whole until all these people are back with their families and in their communities.

Earlier you mentioned how you learned to ideate properly. How did that apply here?

My sister is an electrical engineer, and she contracts with the military. She develops training modules for our soldiers, almost like a 3D AR/VR experience, where they can simulate being in war. It’s very intense. I was really hitting her for insights about how it feels for someone to be on the ground in battle. Is there a fear factor that you have to work into these simulations? How do you mentally prepare somebody for that?

A lot of the creative process was trying to understand what was in the heart and mind of a soldier. Why would he want to dedicate himself to that? If he’s able to survive the battle what happens when he gets back? There are heartbreaking stories about people who can’t find jobs or can’t figure out how to assimilate back into their family’s lives because so much time has passed and so many things have been missed.I shared all that with my team to help them work through it. We worked through a lot of ideas. Sometimes it’s just about asking, “Is this language right? Is what we’re saying really true? Will someone see this and say, ‘They know my experience. They really know what I’m going through?’”

It took some time in that process to get there. But, as a creative myself, when I feel like I’ve got the words right, I usually get a little bit of a tingle in my neck when I read it to myself out loud. That’s when I thought, Ok, this might be going somewhere.

That seems like a pretty good litmus test.

It’s so important to find your voice as a creative. The industry may tell us to chase a trend or a fad, to run towards that shiny object. But, the best way to get authentic work out of yourself and make things you’re really proud of is to be true to your voice. And be true to the message that you’re putting out. Make sure the message is authentic, thoughtful, and has an empathetic reason to exist.Vida isn’t the only one creating change through her work. Read our conversation with DAVID Miami’s Creative Director Fernando Pellizzaro as he talks about his own impactful projects.