What does it take to turn a childhood love for movies into a thriving career in film and commercial directing? For Al Benoit, the journey began with his grandmother’s Sunday movie rituals and a fascination with the emotional power of storytelling.

From his early days shooting weddings to directing campaigns for household names, the career of Al Benoit has been defined by a commitment to authenticity and a relentless pursuit of creative growth.

Read more insights from Al Benoit and his refreshing perspective on the art of storytelling and the challenges of navigating the ever-changing landscape of commercial filmmaking.

FILMSUPPLY: How did you get your start in the industry, and what sparked your initial interest in film?

Al Benoit: It all started with my grandma. Every Sunday, we had a routine—lunch at a diner, where she’d stash extra bread in her purse for the ducks at the pond, followed by a trip to the movies. But the funny thing is, we usually didn’t even know what was playing. We’d just show up and pick whatever was starting soon.

That meant I ended up seeing all kinds of movies—different genres, different styles—some things I probably shouldn’t have seen at that age.

But that randomness made it exciting.

And seeing the movie wasn’t the end of it. On the drive home, she’d always ask, “So, if the movie kept going, what would happen next?” If I wanted to see a film, I had to dream up my own sequel.

That simple game stuck with me—it made me think about stories beyond the screen, about what makes a world feel alive.

As I got older, my obsession with movies only grew, and in middle school, I fell headfirst into horror films. I’d rent them from this mom-and-pop video store called Video Villa, knowing full well I was going to terrify myself for days. But that was the rush—it fascinated me that a film could have that kind of hold on you, that it could follow you home.

I couldn’t get enough.

I wanted to understand how a story, a series of images, could create such a visceral emotional reaction. And more than that—I wanted to do it myself.

That passion led me to Columbia College in Chicago, where I studied film. After graduating, I knew I had to throw myself into the deep end, so I packed my bags and moved to LA.

I had no money, no job, no real contacts—just a determination to be around talented people and somehow make it work. So I started emailing and walking into production companies, telling them I’d do anything—get coffee, clean toilets, whatever it took. I just wanted to be in the room.

Eventually, I landed a gig at a small, up-and-coming production company called We Are Famous (unfortunately not around anymore).

It wasn’t glamorous, but I was directing, shooting, editing, writing—whatever they needed. A lot of it was social content with influencers, which was a wild arena to work in, but to me, it was something.

RELATED READS: The Story’s The Solution: Taking Branded Content Further

I think I was making about a hundred bucks a day at first, but that was enough to quit my job at this cheese shop in Venice and throw myself into it full-time.

We basically lived in the studio—it was a handful of us, all young, grinding, figuring it out, and having a blast making things. That time taught me a lot—how to think fast, solve problems, work with big personalities, and make something out of nothing.

It wasn’t the traditional way in, but it gave me a foundation.

RELATED READS: Show Your Work: A Strategy for Self-Promotion

How did your early work with high-profile clients shape your career?

Al Benoit: When I was working at We Are Famous, the owner was, Josh Greenberg, an eccentric but incredibly driven guy. He saw how hard I was working—probably because I was literally sleeping at the studio three nights a week—and he liked my hustle.

After some time, two bigger projects landed on his desk. And instead of passing them off to someone more experienced, he decided to take a chance on me. He figured I was ready enough.

And if nothing else, I’d learn a lot.

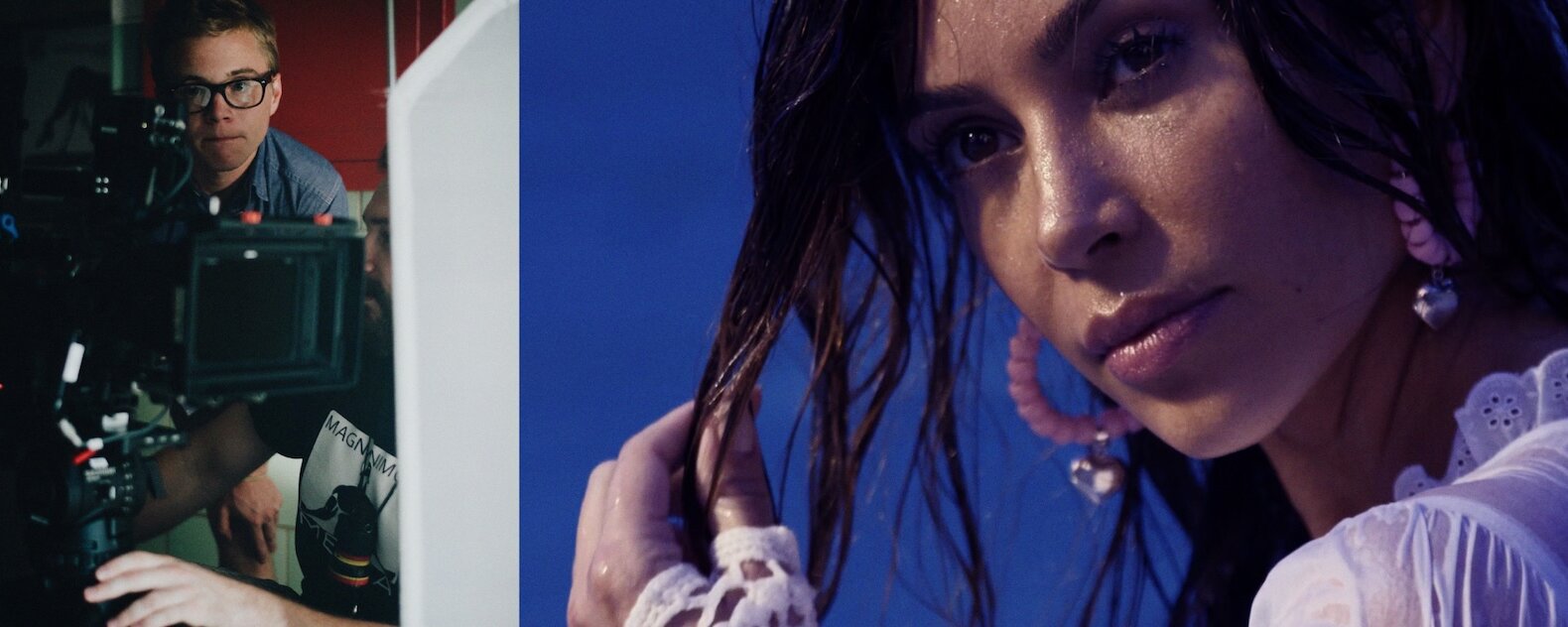

The first project was for Wonderland Magazine, shooting a video piece alongside a Kim Kardashian cover shoot. I called up my best friend and DP, Jonah Rubash, and we found ourselves driving up to this massive mansion in the Hollywood Hills, rolling through presidential-level security just to get to set.

I was 23 at the time—still green, still figuring it all out—but I was there to direct.

RELATED READS: Director Manjari Makijany on Finding Commercial and Narrative Success

The shoot itself went smoothly, but I was definitely nervous as hell.

Part of the job involved sitting down for a one-on-one interview with Kim. It was just me and her in this private home theater, with her manager, publicist, and security looming behind us.

I had my list of questions, and inside, I was shaking, but I kept my cool (somehow). She was surprisingly personable, answered every question thoughtfully, and treated the conversation with real ease.

That moment taught me something huge: working with high-profile people isn’t about being intimidated; they’re just people. If you walk in prepared, with something to say and a clear vision, they’ll listen. That realization gave me a confidence I didn’t have before.

The second project was a TV commercial for Smart Water—my first real spot. It was a whole different beast.

It was a three-day shoot with three professional athletes, and suddenly I wasn’t just dealing with a small, scrappy team. I was in the deep end with agency people, clients, and a whole video village of execs watching my every move.

Up until that point, I had only done my personal short films and social content. It had been my vision and my creative direction with no one else to answer to. I naively thought that would fly in the commercial world, that the agency and clients would just trust what I was doing.

It was a trial by fire, and looking back, I didn’t handle it as well as I should have.

Big mistake.

I quickly learned that in commercial directing, you have to be in sync with everyone—the agency, the client, the brand—because they all have their own vision, their own pressures, and their own people they answer to. I wasn’t communicating enough with them, wasn’t checking in at video village, and wasn’t bringing them into my process the way I should have.

And they noticed.

I’m pretty sure they never called me back after that job. But honestly, it was one of the best learning experiences I could’ve had.

Afterward, Josh sat me down and we had a long talk about what I did wrong, what I learned, and how I could grow from it. That moment shaped how I approach commercial work to this day.

Now I know that commercial directing isn’t just about having a strong creative vision—it’s about melding that vision with the agency and client’s needs and making sure everyone feels heard. I had to learn that lesson the hard way, but it’s one that stuck with me.

RELATED READS: 5 Elements of Giving Effective Feedback

What have you learned throughout your career that has shaped your approach to storytelling?

Al Benoit: When I was younger, like everyone starting out, I didn’t really know what I was doing as a writer. (Honestly, I still don’t!) It’s something you’re always learning, always evolving in.

But what I did know, even back then, was that I wanted to tell stories through film. And the only guiding principle I had was this:

Tell something personal. Something exposing, something that feels like a diary on screen.

That was the only way I knew how.

But storytelling isn’t just about what’s in the script. And I think I started to really understand that through an unexpected avenue: shooting weddings.

During film school, I had to make money, so I started taking wedding gigs: filming, editing, the whole thing. Now, I know that doesn’t sound like it has anything to do with storytelling, but stay with me here!

RELATED READS: Karen Kourtessis on Why Every Project is an Opportunity to Grow as an Editor

I come from a narrative background, but I treated weddings like mini-documentaries. No staged shots, no posed moments. I’d spend time with the couple beforehand, get to know them. And then I’d just live the day with them, shooting every little and big moment as it naturally unfolded.

That taught me something huge: you can’t force real moments. You have to be present enough to capture them because, when you’re shooting docu-style, there are no do-overs. You either catch the moment or it’s gone.

That instinct—the ability to find truth in real-time, to frame life as it’s happening—became a huge part of my approach to filmmaking.

It taught me how to listen, how to work with actors as real people, and how to recognize the kind of small, beautiful moments that feel alive on screen.

“You can’t force real moments. You have to be present enough to capture them because, when you’re shooting docu-style, there are no do-overs. You either catch the moment, or it’s gone.”

Al Benoit

Even though I wasn’t directing scripted pieces at that time, I was still learning how to look for truth on camera. And in many ways, it reinforced the type of storytelling I had first fallen in love with as a kid—nd then again in film school.

I became obsessed with filmmakers like John Cassavetes—his cinéma vérité style, his rejection of formulaic storytelling, his ability to make everyday life feel cinematic. His films weren’t polished or structured in the traditional sense. But they were alive—full of raw, real, unpredictable human moments.

And that’s what I chase after in everything I do.

Even in commercial work, I try to bring that same spontaneous, authentic energy. Maybe I can’t apply it to the entire spot, but I’m always looking for ways to sneak in those truthful, magic moments.

I try to empower the subjects to bring their own experiences and interpretations, creating space for something real to happen. Because at the end of the day, the best storytelling—whether it’s narrative, commercial, or documentary—comes from truth.

RELATED READS: The Hard Truth: YETI’s Scott Ballew on Authentic Storytelling

How does being both a director and editor influence your creative decisions?

Al Benoit: I try to wear my editing hat when I’m writing and shooting. I try to have a clear idea of the final cut in mind, but I also know that I won’t truly strike the right balance until I’m in post.

That awareness informs everything I do as a director—especially when it comes to getting proper coverage.

Before I started directing more, I spent a lot of time in the trenches of editing. And let me tell you, there were a few times directors left us in some brutal spots. I’d get into post and realize I didn’t have the right material to work with, which meant reconfiguring the whole piece in the edit.

That put pressure on me, my team, the clients, and the project as a whole. And I just always thought, “Man, I would never want to do that to an editor.”

So now, I’ve got this split personality thing going on—two versions of me. Director Al is on set making creative decisions. Meanwhile, Editor Al is in the back of his mind, saying, “You better get this shot, or I’m going to be pissed later.” And trust me, Editor Al still gets pissed at Director Al sometimes—but hopefully less and less!

RELATED READS: Editing with a Director’s Perspective

That probably sounds kind of pretentious, but I swear it’s not. It’s just about thinking through everything from both perspectives—making sure I’m giving the editor (whether it’s me or someone else) enough material to craft the best piece possible.

Beyond just getting the right footage, being an editor also helps me detach from my own directing when it’s time to cut.

A lot of directors fall in love with their shots—the long, beautiful camera moves, the epic compositions. But sometimes, that just doesn’t serve the story, and you have to know when to kill your darlings.

That was a hard lesson for me, and one I’m still learning.

A lot of commercial directors are obsessed with making their “director’s cut,” but I don’t really think that way. My job is to deliver the best possible piece in the time we have. If it serves the story, it stays. If it doesn’t, it goes. Simple as that.

RELATED READS: Follow the Edit: Key Insights on Letting Your Project Lead the Way

What major shifts have you seen in commercial filmmaking, and how have you adapted?

Al Benoit: The biggest shift? Tighter everything. Tighter timelines, tighter budgets. But somehow, the expectations have only gotten bigger. Clients want the world, but they want it fast and cheap—and that’s just the reality of where commercial filmmaking is right now.

There was a time when you’d have weeks to prep a job properly. Now you’re lucky if you get a few days. The turnaround from shoot to final delivery keeps shrinking, and at the same time, the number of deliverables has exploded.

RELATED READS: The Insane, 100-Day Production Behind ESPN’s ‘Draft Academy’

It’s not just a :30 or :60 spot for TV anymore—it’s social cutdown, behind-the-scenes content, interactive pieces. And each of them needs to be tailored for different platforms, different audiences, and different aspect ratios.

You have to be thinking about every version of the piece while you’re shooting it, which completely changes the approach.

And honestly? It’s a tough time for a lot of great production companies right now. We’re seeing studios close left and right—places that have been pillars in the industry for years.

I just went through that firsthand when The Mill (worked there for six years) shut down overnight. It was a shock. So many brilliant, talented people are suddenly out of work. It’s a reminder that nothing is guaranteed in this industry.

You have to stay adaptable, stay ahead, and stay connected.

One of the bigger problems I’ve seen is the race to the bottom. Companies will undercut each other, promising they can do the same job faster and cheaper just to land it.

RELATED READS: TCO London’s Senior Producer Josh Hillman on Producing Under Pressure

And sure, maybe that gets you the gig, but at what cost? You’re probably taking a financial hit, stretching your team thin, or sacrificing quality. And once you start down that road, it’s hard to come back.

Suddenly, budgets across the board shrink because clients expect everything to be done for less. It becomes a never-ending cycle.

That’s how you get production companies taking projects just for “exposure,” knowing full well they’re not actually gaining financially from it. And that’s dangerous. Because at the end of the day, exposure doesn’t pay the bills.

If we keep lowering the bar just to stay in the game, we’re devaluing the very thing we’re trying to build.

That’s why my focus has been on adapting without compromising. I try to work faster and smarter and figure out ways to keep the quality high, even when the resources are shrinking.

It’s about being prepared to pivot, whether that’s adjusting creative to fit the budget, finding scrappy, efficient ways to execute, or just knowing how to keep cool under pressure when things inevitably change last minute.

But for all the challenges, I think there’s real opportunity, too. There are more avenues than ever to put creative work out into the world: TV, digital, social, streaming, experiential. The barrier to entry has never been lower, which means more voices, more perspectives, and more ways to tell stories.

It’s just about knowing how to navigate the chaos and make something great in the process.

RELATED READS: The Future of the Commercial Industry

What’s been the most rewarding project of your career?

Al Benoit: Two projects come to mind for different reasons.

The first was a piece I directed for Chicago’s Off The Street Club, a fundraising campaign for the city’s oldest inner-city youth program. The club is a safe haven for over 3,000 kids in West Garfield Park, a neighborhood where violence, gangs, and drugs are a daily reality.

But at Off The Street Club, the focus is different: it’s about hope, joy, and giving kids a chance to just be kids. Their motto is “Every young person deserves to experience casual joy,” and that mission really stuck with me.

Getting to spend time with these kids, hear their stories, and capture their energy and resilience on camera was something I’ll never forget. It felt like I was doing something bigger than myself, something worthwhile.

And when the campaign helped them reach their fundraising goal, it was one of the best feelings I’ve had in my career.

RELATED READS: GS&P’s CCO Margaret Johnson: One Project That Helped Define Her Career

The second project was rewarding for a completely different reason. It was one of my first short films outside of film school, without the school’s backing or access to their equipment.

I had to raise every dollar myself, running a Kickstarter campaign to scrape together a budget. It wasn’t much, but it was the first time I had any real resources of my own to work with.

The film was called We Were Monsters and Detectives, and I poured everything I had into it.

What made it even more special was that so many of my film school friends came together to make it happen. None of us were getting paid a dime, but that didn’t matter—we just wanted to create, tell a story, and prove to ourselves that we could do this on our own.

It was a project made entirely for the love of filmmaking.

RELATED READS: The Real Value of Taking on Passion Projects

I learned so much about myself and about being a filmmaker through that experience. And when we finally finished it and got to see it play at film festivals, it was incredibly rewarding.

But what meant the most to me was that I got to dedicate the film to my grandma—the person who first instilled a love of film in me. That felt full circle in the best possible way.

When I get to make my first feature, that will be the next most rewarding moment. It’s what I’ve been chasing since I started—the ultimate goal, the thing that matters most to me.

What advice do you have for editors and directors wanting to work with brands and household names?

Al Benoit: Honestly? I don’t love giving advice because I still feel lost in this industry myself, and there’s really no clear path to breaking in. But one thing I do believe is staying in the game—however you can.

When you’re first starting out, it’s easy to feel like you’re spinning your wheels doing wedding videos, corporate gigs, and random edits for clients you don’t necessarily care about. But I look back on those days fondly because, even though they weren’t the “dream projects,” they kept me practicing, kept me learning, and kept me in the industry—even if it was on the far fringe.

RELATED READS: How to Make Branded Content Without Losing Your Soul With Evolve Studios

Every project, no matter how small, is an opportunity to sharpen your instincts, stay current with new technology, and, most importantly, learn about people.

A wedding video might not feel like storytelling in the traditional sense, but it teaches you how to capture moments in real-time.

A corporate gig might not be exciting, but it can help you understand how brands think, what clients care about, and how to navigate that space.

You never know how these experiences will reward you down the line. The industry is small—the people you meet on those early jobs might be the ones hiring you for bigger projects later. The skills you pick up in one space might make you invaluable in another.

So if there’s anything I can offer, it’s just this: stay within the world as much as you can. Keep practicing. Keep making things. Even if you’re on the edges of the industry, you’re still in it. And that’s what keeps you moving forward.

RELATED READS: For Creatives, Scarcity Is an Opportunity

What outside inspirations influence your creative work the most?

Al Benoit: Movies, of course, are a huge influence. I try to see as many films as possible, and I still make it a point to go to the theater as much as I can. Whether it’s new releases or catching older films projected on film at The Metrograph, there’s something about experiencing movies in a theater setting that keeps me inspired.

Seeing a film on the big screen, in the dark, surrounded by strangers—it just hits differently. It reminds me why I fell in love with it in the first place.

But outside of film, short stories have been an obsession of mine. I’m fascinated by the form—by how a writer can capture something so poignant, so rich, in just a few pages. There’s a discipline to it, an economy of storytelling that I really admire.

My apartment is filled with short story collections. They’re stacked on shelves and piled on my desk. I underline lines I love, and later, I go back through them whenever I need a creative spark.

RELATED READS: Storytelling as a Craft: How to Transform Ideas into Thrilling Stories

One collection I keep coming back to is Georgia Under Water by Heather Sellers. I re-read it every couple of months. There’s something about those stories that gets under my skin in the best way. It would be my dream to adapt it to film.

The way she writes—so raw, so human—feels like the kind of storytelling I want to bring to my work.

I think that’s why I love both movies and short stories so much: they’re different mediums, but they both rely on finding the perfect moments to tell a story.

One frame, one sentence—it can be enough to knock the wind out of you. The moments that linger, that say everything in the simplest, most powerful way.

What’s one piece of career advice that has stuck with you over the years?

Al Benoit: I’m sure I got some great advice in film school that I’m just totally blanking on right now (sorry, professors). Shoutout to Jennifer Peepas, Chris Swider, and Paul Peditto!

But the piece of advice that really stuck with me wasn’t something directly said to me, but something I heard at a screening of Sean Baker’s Tangerine.

He did a Q&A after the film. (Tangerine was really blowing up at the time.)

Someone in the audience asked him about his process, and he started talking about the feeling you get between projects—that moment when you think, “Oh, I have no idea if I’m ever going to be able to make something again.”

He talked about the desperation that creeps in between films—the uncertainty, the doubt. Am I going to get another project off the ground? Is this actually going to happen? Even if I can finance it, will I even get inspired enough to make another film?

And then he said something that hit me hard:

“That feeling never goes away.”

I loved hearing that, and I hated hearing that at the same time.

I hated it because, man, even after success, after recognition, you’re still battling that same mental torture? That uncertainty is never going to stop? But at the same time, it weirdly comforted me because it meant I wasn’t alone.

That feeling wasn’t something I was going through because I hadn’t “made it” yet—it’s something all filmmakers and creatives go through.

“Keep practicing. Keep making things. Even if you’re on the edges of the industry, you’re still in it. And that’s what keeps you moving forward.”

Al Benoit

Since then, I’ve tried my best to change my attitude about it. Instead of getting stressed and stuck in the uncertainty, I try to flip the perspective.

Instead of I don’t know what’s going to happen next, and that terrifies me, I try to think I don’t know what’s going to happen next—and that’s exciting.

The discovery, the unknown—that’s what makes it a journey. And those moments where inspiration finally hits? That’s what makes it all worth it.

Why would you recommend Filmsupply as a resource for editors, agencies, and post houses?

Al Benoit: During COVID, when productions shut down, brands still needed content, so editing became even more crucial. A lot of them turned to stock footage, and at first, I was skeptical. Let’s be real—stock footage has a reputation. It can look generic, cheesy, poorly lit, and just … stock-y.

But that’s when I really started digging into Filmsupply, and I realized it wasn’t like other stock sites.

RELATED READS: How Filmsupply Is Revolutionizing Footage Licensing

So much of the footage on there feels cinematic: it’s beautifully shot, rich in emotion, and actually feels like it belongs in a story.

Instead of looking like filler footage, it enhances a project rather than cheapening it. That’s a huge difference.

I think one of the biggest reasons for that is who they get their footage from. A lot of working filmmakers contribute to Filmsupply, which elevates the quality across the board.

The footage is shot with nice cameras and lenses, so you’re not dealing with low-res, overly compressed clips. You’re working with 4K, raw files that allow you to fully manipulate color and make everything feel cohesive. That level of control makes a massive difference.

Beyond the quality, Filmsupply seems to be built with creatives in mind. Their platform is easy to navigate, with great filters, pre-made collections, and even custom curation.

RELATED READS: How Filmsupply Helped Give Nature a Voice for the Royal Ontario Museum

There have been times when we’ve needed something really specific, and we’ve reached out to their reps. They’ve gotten back to us fast with a well-thought-out collection that actually fits our needs. That kind of service is rare.

At the end of the day, whenever I’ve turned to Filmsupply, I’ve felt like I’m actually getting footage that elevates the project. Instead of sticking out like a sore thumb, it feels natural, polished, and intentionally crafted.